Crafting a Political Strategy for Urban Reform

Fourth of a five part series to understand and analyse the (un)design of Indian cities

Contents

Urban Reforms Policy to Politics: An arduous journey

The cardinal sin our public policy intellectuals make, is to expect our politics to sort itself out. They reason, much like them, people change their minds in precense of robust, evidence filled arguments. They expect a high-capacity political system, adept at parsing through abstract ideas and translating ideas into tangible cost-benefit analysis for themselves. Quite a contrast since the rest of Indian institutions are clearly very low capacity. Indian political system can be anything, but high-capacity it is not.

Instead, we Indians much like elsewhere sway to emotions, narratives and soundbites. An effective mobilizer of masses, moulder of opinion will peddle in the same wares. Thus to convince such the politician to adopt certain “pet issues”, a public policy intellectual has to convince the him of its benefits- specifically its potential to evoke a strong “emotion”, render itself to an appealing “narrative”, and lend itself to “catchy soundbites”. In short, a thinker needs to build a political cost-benefit with his policy. A sort of “batteries included” philosophy, so to speak1.

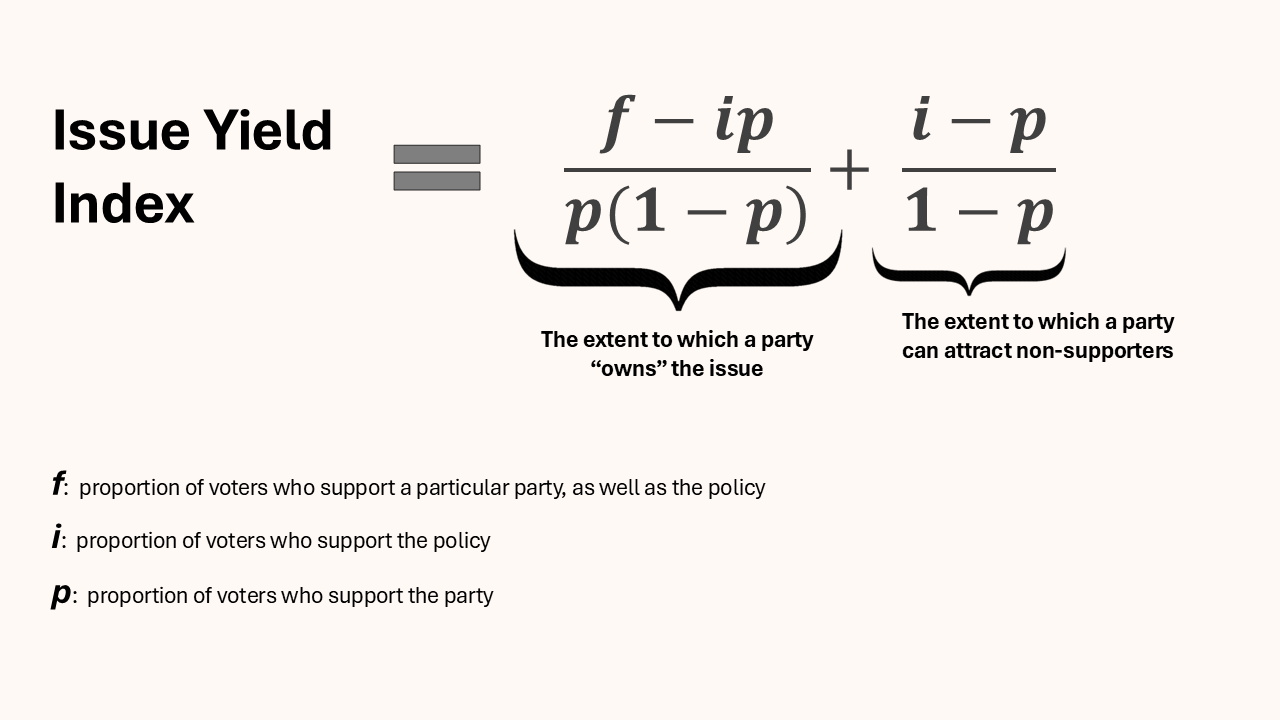

How do we build political cost-benefit analysis for a particular economic proposal? Lorenzo de Sio and Till Weber do exactly this with their issue yield index. They recognize that political parties adopt issues based on how much they “own” it - i.e. how much the idea is related to their identity, positioning, core beliefs of their voters etc. Think about how much do the Democratic Party in US “owns” pro-choice stance vis a vis their opponent, the Republicans do. Similarly, think about how much do the Tories in UK “owned” the Brexit policy in 2016 vis a vis the Labor Party. Sometimes, some issues are “free-for-all”- owned by noone in particular. For example- imagine economic liberalization in India of 1970s.

The extent to which an “idea” is close to the core beliefs of its voters is the extent to which a particular political party “owns” the idea. In general, the paper2 considers that political parties select issues and emphasise them to mobilize core voters and broadening the support base. Such policies that do achieve both, are called bridge policies. When the issues antagonize the core voters, but reach out for the external votes, its called venture policies (since this is risky), which stir neither camps are appropriately named dead-end policies, and which only “pamper” its core voters, are pamper policies.

The Logic of Issue Yield Index

Consider a system where there are only 2 political parties A and B. Let’s consider the analysis from the view point of political party A, of whose core voters, a proportion f support a particular policy P. In general, across the electorate the same policy P, enjoys a support of i, where,

Further, consider that a p proportion of the general electorate support the party. So at least, we know theoretically,

Now, pay attention to the quantity ip. Had the supporters of a particular policy been porportionately spread across the 2 parties, there would be ip number of supporters of both the policy and the political party. Thus if f = ip, it implies the party doesn’t really “own” the issue. However, if f-ip >0 , that is the extent to which the party “owns” it.

This is the variable that every party would like to preserve - they represent the core voters and the policy is most preferable to them. However, consider the quantity i-p: this represents the number of potential supporters outside the fold of the party, as far as this policy is concerned. An effective political party would also like to appeal to this group.

So, how much “voters” a particular issue yields is the combination of the two quantities “f-ip” and “i-p”. However, to normalize the respective “drivers” of support, the authors have scaled individual drivers by their maximum value.

Just a quick check, what happens when all the supporters of a particular policy are already the supporters of the party and noone disagrees with the policy? The three variables, f, i, and p becomes equal. This also makes the catchment area outside the party, the second term i-p as zero.

What happens when the entire electorate agrees with a particular policy, i.e. i = 1? The first term turns zero (since there is no one who disagrees with the policy inside the party, thus f=p and i=1) and the second term becomes 1.

For perfect bridge policies, a party is able to keep its own voters, and attract other supporters too, thus making the issue yield as +1. For perfect dead-end policies, that pleases no-one, the issue yield is -1 (that is it will lose all votes).

The researchers found strong evidence of that parties emphasise specific policy based on their ability to retain and attract voters. This is captured robustly by issue yield index in a 2 party and multiparty systems. In a multiparty system, there is an added issue of effective number of parties(ENP) and effective number of issue competitors (ENC). A party which owns an “issue” will have very low ENC i.e. not many can effectively compete against it on the issue, while parties who do not quite “own an issue” (think: anti-crime policy in US) will have large ENCs, i.e. it is competing with everyone.

While this is a Cliff’s Note version of the paper, I recommend the enterprising reader to read the paper. A copy of the paper is available for reference here.

Urban Reforms and its Issue Yield Index

In Indian context, I propose urban reforms are a promising bridge policy. 520mn Indians today are living in urban areas, that’s roughly 33% of Indian population. Rural India is also benefiting from the emergence of urban areas, as labor moves seamlessly into and out of urban areas depending on the farming season and short term economics.

If urban reform is advertised appropriately, the a wide cross section of Indian voting population is expected to support such a policy. Further as of today no single party “owns” the issue. This implies, for a smaller party, there is considerable benefit in emphasising this issue - there is a large catchment area outside their traditional support, which makes it attractive for them to pursue such policy lines. For newer parties, it makes similar sense to latch onto themes of widespread dissatisfaction. They do not have a constituency to maintain and thus can position themselves effectively to appear attractive to traditional voters of other parties. The focus on efficiency delivery of public services appears well-supported in practice (e.g. Aam Aadmi Party emphasised on mohalla sabhas, an avatar of direct democracy in an attempt to decentralize decision making, and improve governance; Jan Suraaj Party is emphasising on School Vouchers etc.)

Fixing Our Intuition: 3 Examples

Let’s try to fix our intuition. Today, ~33% of the population is living in urban areas. There will be a very large support for urban reform in this subset. The rest 65% of the population benefits from positive spillover effects of urbanization. Lets consider 20% of the rural population actively support urban reforms, having recognized its positive effects on their income levels.

Assume there are 3 parties in the society:

a party that espouses majoritarian philosophy(Party M),

a political party with centre-left philosophy (Party C), and

a political party that practices identity/empowerment principles (Party I).

Further consider Party M is the ruling party, with roughly a little above third of national vote share(support of 1 out of 3 members of the general electorate). Party C does a little worse, it enjoys the support of 1out of every 5 voters. Party I is a much smaller party and it has a 1-in-20 support.

Lastly no party “owns” the policy proposal. Thus the issue yield index completely depends upon the size of the catchment area outside its traditional support base.

To simplify the analysis, when analysing the issue for each party, every other party will be clubbed together, to form effectively a 2 party system. This simplifies our analysis and helps us understand the issue yield index for each of them.

Let’s consider the policy statement P- “We need sweeping urban reforms for our cities”

Analysing Issue Yield of the policy statement P for Party M

As per this table:

f, proportion of voters supporting both the policy and the party (16%)

i, proportion of voters supporting the policy across the party lines (48%)

p, proportion of voters supporting the party (33%)

Thus f-ip = 0 and the issue yield index goes to 0.61, a positive number, driven completely by the ability of Party M to “draw” supporters of other party to its fold because of this issue.

Analysing Issue Yield of the policy statement P for Party C

As per this table:

f, proportion of voters supporting both the policy and the party (10%)

i, proportion of voters supporting the policy across the party lines (48%)

p, proportion of voters supporting the party (20%)

The issue yield index goes to 0.74, a positive number, and higher than that for Party M, symptomatic of a “larger” catchment area for Party C to attract its potential voters.

Needless to say, when we do the same exercise for an even smaller party, Party I, the number should be higher.

Analysing Issue Yield of the policy statement P for Party I

As we would expect the issue yield index is 0.87 for Party I.

What does High Yield Index reveal for Indian Political Parties?

It is profitable for a small party struggling to make its precense felt, to adopt secular issues of public misgovernance. Why political parties settled for catalysts of misgovernance, criminal elements as representatives of people, remains a question 3

While it is profitable for smaller parties to emphasise on issues of public goods, they may not be able to attract voters due to poor credibility. Thus a smaller party should burnish their credentials along with emphasising on promises of public goods. It doesn’t help that centralization has left very little autonomy for a small party to credibly deliver on its promises.

From Policy to Praxis: The Missing Link

To move from policy to law, requires one to weave a treacherous journey through the art of narrative. While issue yield index showed which policy proposal a particular party to should persue, a politician still doesn’t know to push a particular issue into the zeitgeist. Not many political leader have shown an ability to redefine the mood of a country to their advantage. Far fewer have been able to ride it profitably. Deft politicians are well-versed with the art of crafting compelling narratives.

Can we craft one such narrative of our own? We can definitely try.

Narrative Policy Framework is a particularly interesting idea in this quest. Kuenzler et. al4 define it as “a theoretical approach within the academic field of public policy that was originally designed to scientifically assess the role of narratives in the policy process.” The framework both identifies and prescribes narrative strategies of succesful political movements. Compelling political movements like Soro Soke, BlackLivesMatter, MeToo, Ram Janmabhoomi Movement, India Against Corruption movement all have a common narrative structure. Much like the shape of stories as brought to our attention by Vonnegut5, NPF charts out the 5 element structure of political narratives- the setting, oulined by socio-economic context, institutional imperatives, and policymaking backdrop; “hero”, the key driver of the plot; the “villain”, the key antagonist force which is preventing the change, and the plot itself, a simplistic, reductionist tale, whose moral is the policy proposal.

Empirically, narratives are most effective when it rides on audience’s fundamental beliefs. The end goal being to piggyback on the voters’ fundamental beliefs to shape their more malleable outlook. With this backdrop, it suddenly makes a lot of sense why politicians in India emerge successful after they either do padyatras, cross-country journeys or visiting rural India - to get a ‘feel’ of the fundamental beliefs of the society. M.K. Gandhi emerged as a national figurehead after he took Gopalkrishna Gokhale’s advice to travel across India to heart in 1915. He further renewed his and Indian National Congress’s political capital after Civil Disobedience Movement by exhorting Congressmen to go back to Indian villages. Many modern politicians have witnessed a resurgence in their vote share after performing such cross-country travels.

Historical anecdotes aside, NPF poses a unique conundrum for Indian contexts. India is a deeply fractured society. Lazy politicians have long capitalized on these cracks to drive their narrative. Its easy to find an “other”, and villainize them. NPF needs a tangible easy villain. Yet there are signs that Indian society has developed a fatigue for “villains”. If a politician is able to create a narrative without a villain, he will be able to create a potent contrast effect.

I am no politician, and I do not have the gift of story telling. I cannot build a narrative out of the blue. Yet, we do have something that is uniquely poised to generate creative content : large language models.

I asked ChatGPT-4o to build a narrative for a small South Indian political party based on positive vision for the future and non-victimhood. While it spat out an interesting answer, which can be found here6, I am adding the key aspects of the narrative. Pertinent to note, the LLM couldn’t quite do away with villainizing, but it villanizes bureaucratic controls, legacy policies, and centralization - non-human targets and the real enemy in our path to progress.

It identifies the key beliefs of the Indian masses as the “dharma of self-effort”, "aspiration for stability”, “strong local identity rooted in urban pride” (cites- Puneri humor, Coimbatore’s manufacturing sector etc.) and value consciousness.

Yet the most interesting rallying cry that LLM proposed was this - “They said reform was Delhi’s job. We say reform is our duty.” It is both mission-oriented, optimistic, eschews victimhood, gives the people agency, and might just goad people into forging a common consciousness.

Specifically, the model suggests specific slogans for the specific reforms that I proposed in the factor reform piece. While it makes a few mistakes e.g. it confuses creating a local credit institution as the solution to reform the capital market, sneaks in reference to “Tamil” pride while the original prompt didnt mention any specific state, and some of its slogans don’t quite “stick” - it is a helpful jumping point for an enterprising party worker to tweak around with it.

From Here to Where: The Next Steps

In this post, I have tried to push forward two key ideas - public goods are attractive ideas to adopt; and we can build effective narratives around them. The framework is there, the ideas are all there: all it needs is an effective politician to pick it up and run with it.

The missing piece in all of this, is how to deliver and signal credibility. Perhaps that is the key reason why no political party has tried its hand at this. Mix it in with the problem of long gestation periods for systemic changes to show up - we are staring at a toxic mix of low trust and low patience. Perhaps the greatest challenge is, how to win elections after reforming, especially as results are slow to show up, little to start with, people are impatient and credibility is often low to begin with.

However, I posit, that are some elements of urban reform(e.g. police reforms) that can reveal results within 5 years, a typical term for various state level administrations.

Final Words

There is considerable hope that India’s democracy will see a second wave of political parties, with the first wave that started post 1980s. There are indications that these young political parties are thinking afresh, innovating on their pitch and presentation, and unafraid to offer new ideas (school vouchers have entered Indian politics).

There is considerable hope that one of those parties will understand the tremendous benefit to reap by targetting such issues of common concern.

Python, a popular programming language, packages plenty of useful libraries in its installation file, thus letting a beginner use it right from the get-go, without any additional installations. Its founder Guido Van Rossum called it - “batteries included approach”. Similarly, an intellectual has to package his idea with a narrative, slogan, political cost-benefit kit too- so that any politician can adopt it straight “out of the box”.

De Sio, Lorenzo, and Till Weber. "Issue yield: A model of party strategy in multidimensional space." American Political Science Review 108, no. 4 (2014): 870-885. (link)

pg 161, Vaishnav, Milan. 2017. When Crime Pays: Money and Muscle in Indian Politics. Noida Harpercollins Publishers India. (link)

Kuenzler, Johanna, Bettina Stauffer, Caroline Schlaufer, Geoboo Song, Aaron Smith-Walter, and Michael D. Jones. "A systematic review of the Narrative Policy Framework: a future research agenda", Policy & Politics 53, 1 (2025): 129-151, accessed Jun 1, 2025, https://doi.org/10.1332/03055736Y2024D000000046